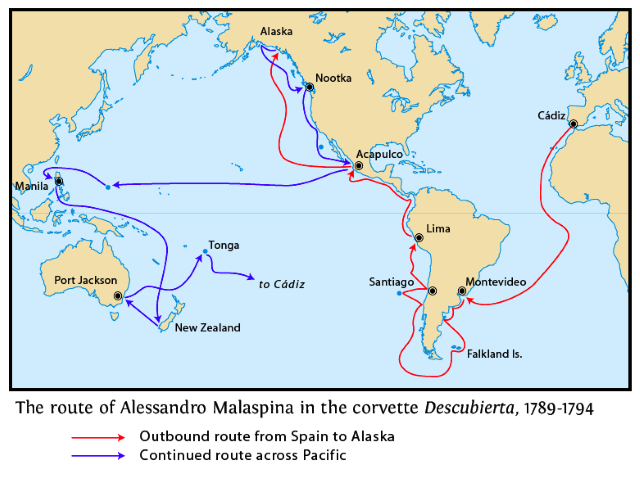

Alessandro Malaspina was a navigator and explorer in the service of Spain whose greatest journey was undertaken between 1789 and 1794. Imprisoned by Spain on his return, he was released through the intervention of Napoleon Bonaparte acting on advice received from Francesco Melzi d’Eril, Vice President of the Italian Republic.

Returning to Italy, between 1804 and 1805 Malaspina acted as the Italian Republic’s General Commissioner for Health responsible for the department of Crostolo (Reggio) together with the territories of the annexed Duchy of Massa & Carrara incorporating Aulla and various municipalities of the former Feudal Lunigiana. In response to an outbreak of yellow fever at Livorno in December 1803 he rapidly created a string of emergency isolation hospitals and arranged for French troops of the line and the National Guard to seal off the border in a successful project to protect the general population from infection.

Personal remarks

Full details of this remarkable man are available elsewhere on the Internet – for example, the Wikipedia page can be found here. He was born the third son of Carlo Morello and Caterina Meli Lupi di Soragna and also had two sisters – one became a cloistered nun in Florence and the other (Metilda) married and lived in Benevento. On his death he left most of his estate to Teresa, Metilda’s daughter.

Worth a visit is the Alessandro Malaspina museum at Mulazzo, not so much for the exhibits (which to be frank are somewhat humdrum) but to sit through the excellent hour long multimedia presentation. Although this is delivered in Italian it is still comprehensible to those English speakers who have done a bit of homework beforehand. Sadly, the museum’s long time director, Dario Manfredi, is no longer alive. He was recognised as being the world authority on Malaspina, producing books and many articles on the mariner’s life and times. An English language translation of his master work as hosted by the Alexandro Malaspina Research Centre at Vancouver Island University is available here.

I first came across the name Alessandro Malaspina whilst touring the South Island of New Zealand in 2011. The entrance to Doubtful Sound (which is in fact a fiord) is named Malaspina Reach. Captain Cook discovered the sound in 1770, but didn’t enter because he doubted his ability to sail back out to sea once inside. On his 1793 visit, Malaspina sent a launch into the sound to carry out a detailed survey from which were produced the first maps of the area.

Malaspina was a humane polymath, a believer in the innate superiority of aristocrats, and a promoter of absolute kingly rule who enthusiatically (and paradoxically) embraced many of the ideas of the Enlightenment (particularly those of Rousseau and Adam Smith). Although a respecter of indigenous peoples he nevertheless had a eurocentric, and often dismissive, view of their culture.

After examining the political situation of the Spanish colonies in the Pacific, Malaspina concluded that instead of plundering them economically, Spain should develop a confederation of states each allowed to conduct international trade. Furthermore, he suggested that Spain should abandon the military domination of far-off lands and establish a Pacific Rim trading bloc, managed from Acapulco by Spaniards. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Malaspina’s views were regarded at best as eccentric and at worst as treasonable with the result that he was ignored and the New World colonies were condemned to instability and bloody wars throughout the nineteenth century.

It was a tragedy that in 1796, two years after his return to Spain, Malaspina was indicted for insurrection, stripped of his rank and titles, had his work supressed, and was committed to prison in the isolated fortress of San Antón in La Coruña, Galicia. Finally released in 1802, he used his time in prison to write on the subjects of aesthetics, economics, and literary criticism. Although officially banned from communicating with the outside world, Malaspina managed to maintain contact with his eldest brother Azzo Giacinto III, effectively the last marquis of Mulazzo, and his other Italian relatives via a Genovese merchant called Longhi.

After his release from prison Malaspina sailed to Genova, arriving in March 1803. The family castle at Mulazzo was a partial ruin as his brother, Luigi (an avaricious, indolent and dissolute individual) had transported the marble and much of the better stonework to Pontremoli where he was building a new mansion in via Fiorentina. (Malaspina’s brother, Azzo, had died in 1800 attempting to escape incarceration as a political prisoner in Austrian controlled Venice). Furthermore, the castle was considered to be part of the feud of Mulazzo and thus subject to confiscation by the Republican/Napoleonic authorities. Under these circumstances, Malaspina set up home in a rented mansion in Pontremoli. Deprived of much feudal income and disqualified from receiving any pension arising from his naval service he was short of money and often had to rely on the generosity of friends to maintain his comfortable lifestyle.

Sadly, Malaspina developed bowel cancer in 1807 and died at ten o’clock on the evening of 9 April 1810 in the presence of his friend Antonio Ricci, doctor Jacopo Barbieri, his manservant Vincenzo Bianchi and the friar Domenico Vincenzo da Parma. Jacopo performed an autopsy and found a large tumour in his intestine. Malaspina’s funeral took place in the cathedral and he was buried in the public cemetery of Pontremoli. Within a few years his burial place was forgotten, there being no headstone or memorial to him (though there is now a simple plaque that records the fact of his burial).

Palazzo Malaspina, Pontremoli

The mansion built by Luigi Malaspina can be found in via Alessandro Malaspina, Pontremoli. According to the Terre di Lunigiana web site , the facade is decorated in stucco designed by Pietro Portugalli of Lugano (who also designed the interior) and features a plaque with the well known aphoristic inscription: “Non dir di me se di te non sai, pensa di te che di me dirai” (Say nothing about me if you don’t know yourself, think of yourself what you will say about me) and the date, 1707. The significance of the date is unknown as the building was actually completed in the late 18th century.

The building was until recently the Biblioteca Comunale (city library) and is in poor condition. It was a Carabinieri barracks until the 1990s after which it was taken over by the Province of Massa Carrara who subsequently allowed the Comune of Pontremoli to use it. Various attempts have been made to sell the building which is of 1,800m2 internal area. Even at €350,000 there were no takers, potential purchasers being discouraged by the enormous cost of restoration.

Sources of further reading

There are few English language tomes that record the life and times of Alessandro Malaspina. The main repositary of information in the English speaking world is held at the Alexandro Malaspina Research Centre at the Vancouver Island University, Canada.

The Alessandro Malaspina Museum at Mulazzo has a good selection of letters and other documents amassed over many years. Its long-time director Dario Manfredi’s Italian language biography of the navigator is available in translated form from the Alexandro Malaspina Research Centre referred to above.

The journals of the Malaspina Expedition 1789-94 were made available in English in 2018 and are available from booksellers. They are in three volumes (Cadiz to Panama, Panama to Manila, and Manila to Cadiz), all published by the Hakluyt Society.