It is easy to be blasé about the risks associated with outdoor activities in the mountains. Although in good, stable weather there is nothing to fear, conditions can change rapidly and become treacherous even in summer. Torrential rain is common and the all-enveloping cloud with which it is associated can cause disorientation, especially where paths are indistinct and poorly waymarked.

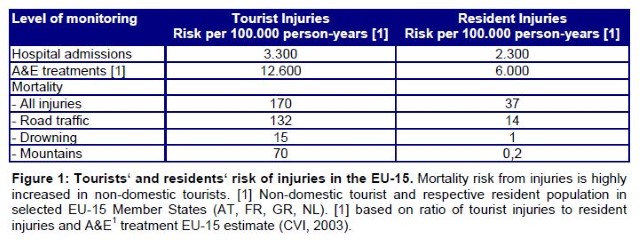

It is remarkable that tourists visiting a country in the EU are five times more likely to have an accident than if they were resident. Even more remarkable, tourists accessing mountainous areas are 350x more likely to suffer injuries. Drilling down into the statistics, one discovers that skiing results in the largest number of injuries followed by rock climbing.

Lightning is also a risk, though meaningful statistics are hard to come by. In the Alps, most lightning strikes occur in June, July and August and there is no reason to believe that the Apennines are different. Very few strikes occur in the mornings and evenings with most taking place between 4 and 6pm. It is therefore sensible to set off early in the morning and to return mid-afternoon.

Table of Contents

Mountain rescue

Mountain rescue in Italy is undertaken by the Corpo Nazionale Soccorso Alpino e Speleologico (C.N.S.A.S.) whose staff incorporate both paid professionals and volunteers. However, the labour-intensive and occasional nature of mountain rescue, along with the specific techniques and local knowledge required for some environments, means that it is often undertaken by voluntary teams made up of local climbers and guides. Paid rescue services commonly work in co-operation with voluntary services. For example, a paid helicopter rescue team may work with a volunteer mountain rescue team on the ground.

A succinct primer on mountain rescue in Italy may be found here. This site primarily relates to the Dolomites, but most of the material is generally applicable.

An excellent documentary explaining the work of the CNSAS is available on YouTube here. (The commentary is in Italian, but don’t let that put you off).

Essential hiking gear you should pack

Before you set out on your journey – whether it be a short day hike or multi day trek – it’s important to set yourself up with the right equipment. Our recommended list for day-hikes is as follows:

- Map & compass

- Mobile phone loaded with “112 Where Are U” app (all-service emergency number in Tuscany is 112 – see details)

- GPS with spare batteries

- First aid kit, mosquito/insect repellent & tick removal tool

- Knife, headtorch, waterproof matches & whistle

- Water (2 litres min for a 4hr walk, 4 litres min for 8hrs)

- Food (high-energy)

- Wet weather gear inc gloves

- Sunglasses, sun hat & sunscreen

- Trekking poles

- Lightweight emergency sleeping bag

Water is key. High up in the Apennines there is little of it. Snow is common in winter and meltwater streams are a feature of spring, but in summer everywhere dries up. This means that to avoid dehydration you must carry substantial quantities of water if walking in the mountains for more than a couple of hours. On two occasions I’ve got into trouble by not taking sufficient water – hot summer days where the route was much more arduous than I’d expected. The result was painful and debilitating cramp – frightening and to be avoided.

There are a few extra bits and pieces that could help you along the way, depending on the length and level of danger of the trail you intend to follow.

- Water treatment tablets to purify stream water should your clean supply run out

- Foldable entrenching tool & toilet paper (sad to report that several mountain huts are surrounded by unburied human excreta – very unpleasant)

- Via ferrata harness

- Lightweight tent that uses trekking poles to provide a frame

Travelling light using a backpack that transfers its weight to the hips is very important, especially for longer trips using a high volume pack. Framed rucksacks have been out of fashion for many years because of their weight, though they can provide excellent separation between one’s back and the surface of the sack so preventing excessive sweat buildup. As regards daypacks, the minimum size we would recommend is 25 litres. The use of a water bladder is not a bad idea as bottles are cumbersome and difficult to pack efficiently. Currently we like the Osprey backpack range but Berghaus get good write-ups, but as ever it’s a matter of personal choice.

Before you set out …

If no one is staying behind at your accommodation, print out a map, use a marker pen to indicate where you’re going, identify where you intend to park the car, and state when you expect to return. Then stick it to your front door and make sure that your neighbours know you are going out. Without this information the emergency services are working blind – remember that the Lunigiana is heavily forested and sparsely populated so it’s particularly difficult to find people who are lost or injured, especially if they’ve wandered off-trail.

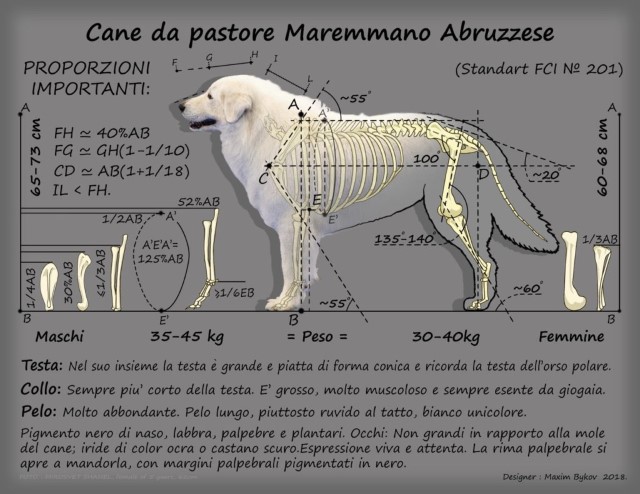

Animals to avoid

Generally it’s very safe to walk in the Lunigiana. There are adders and wolves around, but in 15yrs of hiking through woods, uplands and valleys we’ve never seen either. Large numbers of wild boar can be found everywhere, but they keep well clear of humans. Ticks are reported to be a problem and we carry a tick removal kit, but we’ve never had any bites. (Having said that, we always wear good hiking boots and never wear shorts). The biggest risk is from the large, white Maremmano sheepdogs used to protect flocks of sheep. These are ferocious when their flocks are threatened and are to be avoided at all costs. Never get between a dog and its sheep, and be particularly cautious when there are several dogs protecting a single flock as they have a pack mentality. We always take trekking poles with us on hikes in order to fend off unwelcome dogs, and we’ve had to use them on more than one occasion.