Background & definitions

A fief (fiefdom or feud) was at the core of feudalism. It consisted of heritable property or rights granted by an overlord to a vassal who held it in fealty (or “in fee”). This meant that the vassal was obligated to provide some form of feudal allegiance and service confirmed at intervals by personal ceremonies and acts of homage and fealty. The fees were often lands or revenue-producing real property held in feudal land tenure, typically known as fiefs or fiefdoms. That said, anything of value could be held in fee, including governmental office, rights of exploitation such as hunting or fishing, monopolies in trade, and tax on farms.

A marquis (or marquess) was originally a noble appointed to govern border country. In times past, the distinction between a count and a marquess was that the land of a marquis, known as a march, was borderland, whilst that of a count (a “county”) often was not. As a result, a marquis was trusted to defend and fortify against potentially hostile neighbours and was thus more important and ranked higher than a count. The title is ranked below that of a duke, which was often restricted to a royal family.

The founder of the Malaspina Family was Oberto I Obertenghi (915-975), who became the count of Luni in 945. Oberto I was appointed as the marquis of the March of Genoa under the Italian king Berengario II in 951 and he became a count palatine in 953.

Oberto I had two children; Oberto II (died after 1014) who inherited the title of Count of Luni from his father, and Adalberto I, whose offspring founded the Pallavicino and the Cavalcabò families. Oberto II had four children; Bertha of Milan (spouse of Arduino, King of Italy 1002-1014); Ugo, count of Milan; Alberto Azzo I (ca 970-1029), count of Luni whose offspring founded the Este family branches of Hannover and Brunswick; and Oberto Obizzo I (died 1013), progenitor of the lineage of the Malaspinas.

In 1004, Oberto Obizzo I fought beside his brother-in-law King Arduino against the Count Bishops of Luni. Oberto Obizzo I had a son, Albert I, who in turn had a son, Oberto Obizzo II (?–1090), the father of Alberto Malaspina (?-1140) who was the first member of the family to be called Malaspina; for this reason he is sometimes considered the true founder of the family.

Malaspina rule within the Lunigiana

For centuries the Malaspina family ruled many of the feuds located in the Lunigiana. Their geographical location and size varied dramatically over the years. In large part the changes were driven by the Lombard inheritance rules adopted by the family. These demanded that on the death of a ruler all his male children (other than those who had entered the priesthood) should be endowed with a share of his real estate. In consequence, the family was forever splitting, combining, transferring, buying and selling feuds so as to create politically and economically viable units.

The question arises, with such political weakness afflicting the upper Lunigiana, why didn’t the adjoining stable and powerful states eject the Malaspinas and take control of the lands themselves? There are two reasons. First, the Malaspinas were generally very capable diplomats who were careful who they supported, making astute marriage links to powerful families. More importantly, however, they ruled what was a buffer zone between competing powers – a zone which was a vitally important trade route between the coast and the Po valley, not least for the transportation of the salt required to preserve produce to see the population through the winter months. It was therefore not in the interests of any single regional power to see another such power control the area and potentially hold them to ransom.

It is often said that the Lunigiana contains more castles per square mile than any other part of Italy. These castles were not constructed primarily for military purposes but instead as geographically prominent places of safety and refuge for travellers – especially pilgrims, merchants and representatives of neighbouring powers.

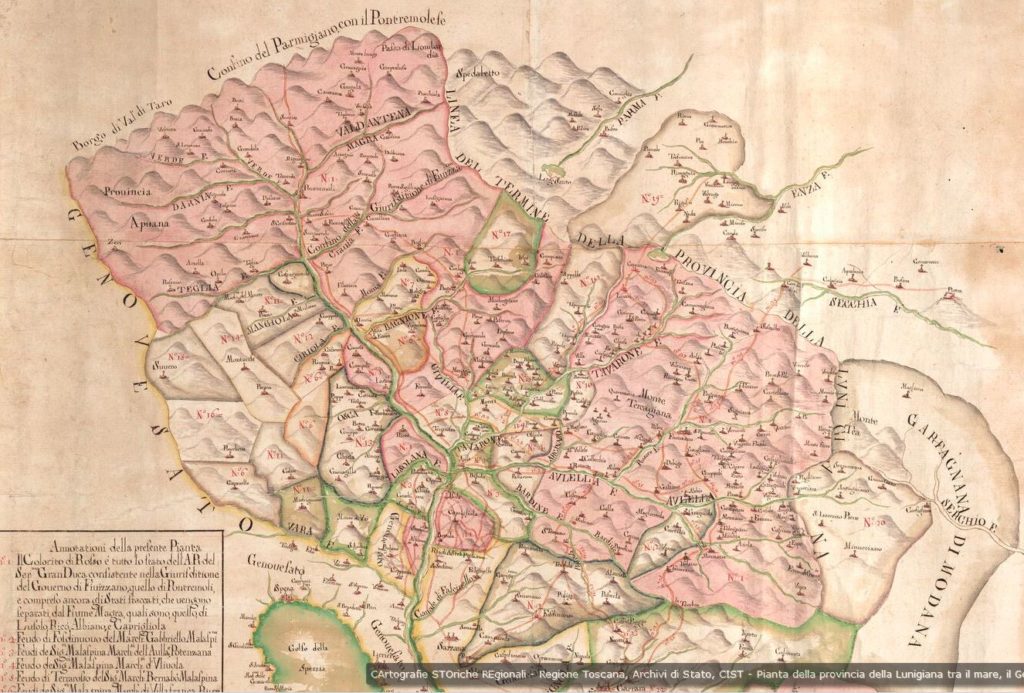

Despite their lack of military strength the Malaspinas retained their lands in the Lunigiana for more than 500yrs in contrast to most of their ilk who over time lost their lands to larger and stronger powers. An indication of the somewhat anomalous situation of the Malaspinas is revealed via the following map of 1499:

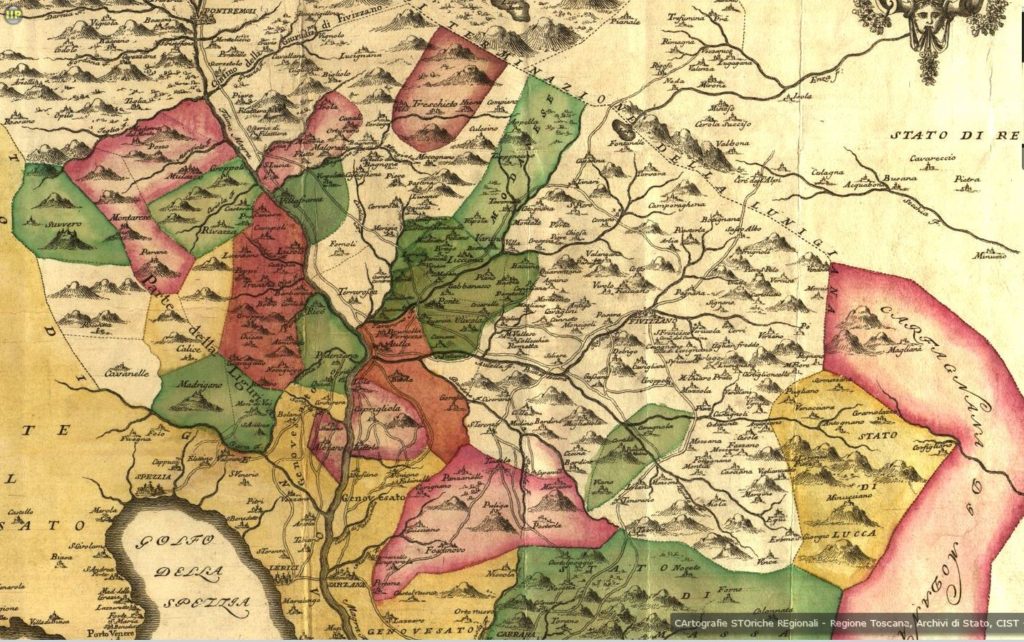

By 1759 there had been some rationalisation of land ownership which is reflected in the map below which was dedicated to Sir Giovanni Manfredi Malaspina, Marquis of Filattiera and Terrarossa. The various owners were:

- State of Genoa

- Grand Duchy of Tuscany

- State of Lucca

- Duchy of Modena

- Duchy of Massa/Principality of Carrara (Cybo-Malaspina dynasty, Dukes of Modena)

- Malaspina family legacy fiefdoms

The map indicates that the only independent fiefdoms in the Lunigiana still ruled by Malaspina family descendents were: Mulazzo, Filetto, Treschietto, Lusuolo and Aulla.

It is worth mentioning that when the Malaspina’s transferred land to other parties they often retained their traditional feudal rights – an example would be the transfer of Filattiera to Florence on 17 March 1549 by means of a contract between Marquis Bernabò Manfredi and Cosimo I.

Some claim that the Malaspinas were entitled to what is known as droit du seigneur giving them the right to sleep the first night with the bride of any one of their vassals. The evidence of its existence is all indirect, involving records of redemption dues paid by vassals to avoid enforcement of some lordly rights. Many intellectual investigations have been devoted to the problem. A considerable number of feudal rights were related to a vassal’s marriage, particularly the lord’s right to select a bride for his vassal, but these were almost invariably redeemed by a money payment, or “avail”; and it seems likely that the droit du seigneur amounted, in effect, only to another tax of this sort.

The ancient fiefdoms of the Malaspinas were abolished under Napoleonic rule and, though briefly they were reinstated after the Congress of Vienna they didn’t survive long, sometimes because there were few direct descendents of the family and sometimes for other reasons. For example, Marquis Azzo Giacinto Malaspina of Mulazzo (eldest brother of Alessandro Malaspina the navigator) renounced his feudal titles in favour of France in 1797. Arrested as a French collaborator when the Austrians briefly re-established control of the Cisalpine Republic in 1799, he died (assumed drowned) trying to escape from the Venetian prison of San Giorgio in Alga c1800 after periods of incarceration at Florence, Mantua and Verona. There is some debate as to whether in 1797 Azzo’s titles passed de jure to his brother, Luigi Tommaso Malaspina (1753-1817), and if so for how long. Confusingly, Alessandro Malaspina was sometimes addressed by the title Marquis after his return to the Lunigiana from Spain. In any event, rule of the March of Mulazzo passed to Massa in 1816 and Massa itself was annexed to Modena in 1829.

Feudalism as such was not reinstated after 1816, though aspects of it continued (especially in Sicily) until well into the twentieth century.